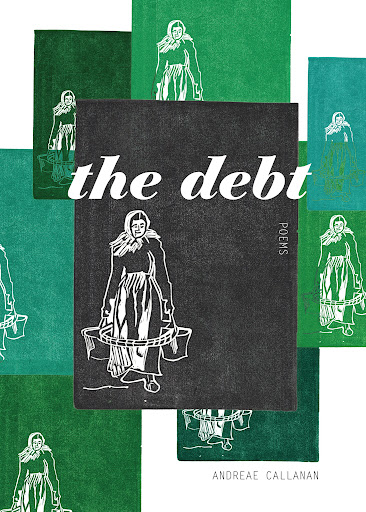

Untangling Andreae Callanan’s “the debt” &

Patrick O’Reilly’s “A Collapsible Newfoundland.”

As I procrastinate preparations to return from Newfoundland to the nuzzle of foothills and the ugly Rocky Mountain wallpaper that is Alberta, I finally got ‘round to reading through two recent offerings from contemporary poets, Andreae Callanan (here in St. John’s), and Patrick O’Reilly (stuck in Montreal), both meditating on Newfoundland, family, and all that usual fodder. Reading the two not so much back to back as side-by-side, which did the thing it does to a brain, entangling the two so that I can’t quite think about one without the other.

My apologies to two poets who deserve to be read meaningfully on their own, but I assure you do no disservice to one another read in such close quarters. Callanan’s “the debt” is out just this year from Biblioasis. O’Reilly’s “A Collapsible Newfoundland is from 2020, published by Frog Hollow Press.

∴

Callanan and O’Reilly are poets with a similarly contemporary sense of Newfoundland poetry, and both situate speakers early in their collections from a post-moratorium, child-like vantage. O’Reilly, in the first of a cycle of poems named for his longed-for ur-home, here “Renews, 1992”, calls out “Marco? / Marco?” only to receive no ‘Polo’ replies, a sense of voicelessness, disconnection from the other, tied to the speaker’s ailing elder relative who, in “the moratorium year…first coughed / [their] blood on the linen” (6). Similarly, in her long-poem “Crown,” Callanan begins her invocation of a kind of rough-throated feminist testimony, embodied by those “Women who’d split a million fish, their throats raw from plant-floor cold”, and standing opposite the speaker who was part of a “Pack of city kids: we couldn’t have known / what no more codfish meant” (14). Both poets magick a voice not of deferral, but instead of understanding, of maturing in a Newfoundland after its most recent governmental dispossession of personhood.

∴

While both poets are mindful of the shortcomings of the tourism brand of Newfoundland, neither shies from enlisting the necessary suspects of the regional genre in both heartening and hilarious turns.

Callanan’s opening poem, “Promise,” travels from its opening lines’ “rumours” to the inquiry of “What / is the sound of twenty thousand / seabirds calling through silken / fog” in a Jeopardy timbre, to the split inflected ask of “promise me” and thwarted potential of “wave-wracked promise” (11), a ginger and thoughtful proposal to the reader, not to tell the reader ‘here we are, bathe in the whelming volume of so-many-seabirds,’ but instead to ask something of us, to vulnerably ask even a clueless mainlander like me to promise this complicated thing that is home isn’t a lie.

O’Reilly’s “The Grouse” relates the “dumbcluck of a bird / fallen on hard luck…unable to finish the joke, unable to fly, / supernaturally unable,” who was “Smart enough to know he was fucked, / never smart enough to get out of it, / you could easily hit a grouse with your boot. / You couldn’t help it” (7). And in “Making Love to Mainlanders,” O’Reilly offers an erotic take on the animal mascotry ascribed to the place: “L’envoi: une petite mort / Wave over wave / over wave over wave: / a million capelin plunging / on the shores of Port de Grave” (13).

∴

While Callanan’s speakers work in a mostly confessional mode, centered around the family, O’Reilly’s poems experiment in a wide variety of registers. Both poets continue to orbit similar thematic territory though, whatever their vantage.

For instance, Callanan recalls mother-made mitts in “Winter,” “Rough / wool, coarsely spun / means our mitts / soak through with each snowball / we shape, each trench we dig” (36). O’Reilly invokes a similar newfoundland knit-ware narrative in “Miss Barnable Recalls,” bringing forth “the thought…of a trigger cuff, soaked and fat with bog” (8).

Both poets home in on the necessity of functional clothing as a matter of mere survival in the Newfoundland weather. Callanan’s meditations come forth in the poem which lends itself to the cover, “The water-carriers”, which details an alien mind attempting to re-rationalize the image of the labouring women with instructions to “make a palimpsest, / sketch slender ribs of steel, crosshatch / horsehair over each bent-birch apparatus, / wrap entire girls in satin and send / them off to dance, callused / unclenched and gloved in kidskin, wrists / wrapped in sapphire circles, in silver, palms / open and idle” (25). In turn, the passing fad of the “Infinity dress,” wherein “the joke / was on us: now we know how fifteen / feet of strap gets twisted and twisted / until the dress is not a dress at all, but / just enough rope” (58), we assume, to hang oneself with. O’Reilly’s Barnable expresses a melancholy about young men and women disappearing into nothingness, “married and whisked off to rooms…nothing ever happened. Nothing was ever admitted, / nothing / was said aloud” (9). As such, the busy knitter Barnable is left with “boxes and boxes / in the attic : socks with no feet to go in them, cuffs with no hands” (9).

∴

News and media serve as ‘proof of an outside world’ for the character’s in “the debt,” whether “The radio whispers us awake,” rousing the sleeping lovers in “Aubade” (45), or details paranoia of nuclear fallout, “her island…half a world away / from those in pictures,” or bad weather bearing down on them from the future, sitting “In front of the TV, in the days of TV, / when the one clear channel channels” (read channel channels out loud and feel its surf, its unbothered whelming woosh), “thrust national news into our living room, / my mother tries to keep ahead of / the weather by building up a stock / of mittens” (36). The above speaker’s mother is a similarly dedicated yarn adept to O’Reilly’s (possible heteronym) Barnable, and “knits with a speed that seems / the stuff of cartoons: heroic, impossible” (37), executing a similar instantaneity to that of telecommunications, the advent of which brought Newfoundland and everywhere else suddenly so much closer to one another than the injuriously isolating rock makes us feel is possible while we live here. In fact, it is the introduction of the TV in the poem that draws Callanan’s speaker’s mother from childhood, wary of catching “flakes on her tongue”, into adulthood and the present in the second stanza, “In front of the TV, in the days of TV.”

In turn, a focus group of mainlanders might expect the newspaper iteration of media to fulfill the archetypal role for a rigorously sea-faring community that we think it should, namely, wrapping fish up in it; fresh cooked fish and chips, dead fish, whichever. But Callanan’s characters in “Crown” instead admit “We wanted to go far away and never look back, / wrap Newfoundland in old newspaper and hide it under / our beds” (23), hiding a sense of inherited inferiority (however irrational it might feel) in not just yesterday’s news, but old newspaper, something you had lying around, piling up. Callanan’s “pack of heathen city kids” (13) feel doubly disconnected from the place they live, on the local scale as townies with “No boats” (14), and the provincial scale as “outpost, not empire” (13). These speakers know they are here in Newfoundland, but are ever-aware of just how close that ‘elsewhere’ feels, the TV which “tells you there’s / another world out there, speaks to you in flattened English,” and which feels so close you may as well just “flatten yourself into an envelope and / mail yourself to Toronto so you can dance yourself sick on Electric Circus” (15).

O’Reilly’s deployment of the paper similarly veers away from the expected cliché, serving as a pseudo-death-shroud in “Bog Body.” Here, “Pop” (we infer ‘grandfather’) is mythologically linked to the “Tollund Man” (10), the most famous of the phenomenon of bog bodies: naturally mummified remains preserved by unique peat bog conditions. What we assume are Pop’s last breaths “made the sound / of bog snatching a rubber boot,” and “When he lay on the daybed” O’Reilly’s speaker notes Pop’s “face / shrouded in the Sunday’s Independent” (referencing the Irish paper). The best naturally preserved body in the history of mankind covered in the mundanity of the Sunday paper, heading to somewhere beyond, somewhere between mythic time and the snapshot of life in a Sunday paper from the old-world. Pop has been reduced to tumbling “through dark ages, / clenched into a seed, / assuming the form of battered leather, / one long sentence without a verb”, but in a moment of great surprise, Pop “Groaned like a king being throttled, / woke up screaming bloody murder” (10). From the mythic, to the soft print of the Sunday paper, and back to life with a ‘crown’ fit for a long poem like that of Callanan.

∴

Neither poet shies away from depicting the historical traumas, nor the plain old difficulties of having cultivated a civilization in this place. In my favourite poem by him, “The Astronauts,” O’Reilly contrasts the historical ‘floating houses’ move against “Kennedy putting cowboys on the moon” (11). Here, “The water is so dark it makes a mirror. / When things get doubled, things get cut in two. / To cut a thing in two’s to break in half” (11). In turn, Callanan’s speaker in “Anniversary” touches on the joy of the interpersonal, the balm of togetherness that withstands reduction and moves the other way: “We fell in love, and I had / to get used to a new kind of speaking / in plural” (66).

∴

Yes, the living here can be hard. As a mainlander who grew up near exactly z e r o major bodies of water, just how wet you can get here, and can’t seem to get dry from, I can vouch that Newfoundland presents its own unique environmental challenges. This is common knowledge to both poet’s speakers, but almost a moot remark in the grand scheme. In “Weatherproof” Callanan’s speakers admit that nasty weather “will come soon and it will /stay long”, but also that they can readily “brace and gird, stay / in, stay warm, take our vitamins, drink / our tea” (48). Likewise, in “Speak of the Dead”, O’Reilly’s speaker approaches aphorism, “the dead can’t be dead ‘til the tea is gone cold. / But, until the death of the weather, / death and the weather will continue, / and anything less than death can be lived with” (16).

∴

It is the mutualism found in hospitality, love, and family that helps speakers weather the sense of Atlantic Canadian gothic degradation that it is often charged with, the “Aluminum siding tacked over softened wood / and flaking paint” of “Renews, 2017” (14), a perpetual problem that is transforming into more complex problems, the above quoted siding now “Like Rubik’s Cubes / left out, every one. Everything the victim of erosion. / The hill lying a little lower than it should.” O’Reilly’s speaker’s desire to return “in ten years time,” worried he’d find himself “still standing here, half wrong, like the H in ghost” (14).

While the speaker’s do persist in all this, the sense of rot, or oceanic annihilation rears its head intermittently between both collections, rendered particularly memorably in Callanan’s cityscape of “Single use.” Here a littered Tim’s cup finds its way to the curb, and the speaker observes “There is purpose / in the rain that swells the cups’ sides, makes loose / their glued seams, turns paper to fiber to pulp / that storm drains strain through iron teeth, then gulp” (65). This image is particularly resonant as it recalls a evocative motif from her earlier poem, “Mantel,” which describes “fat file-folders” with “ridged edges a baleen grin” (33), the biblical whale ever-ready to swallow up the poets and the trash and the whole world, if only the ocean would lap up a little higher along the harbour. O’Reilly’s vision of the future, “saved from what” in “Renews 2121”, proffers a flood, and reminds us “a national literature begins with a flood: / Akkad, Acadia—the epic’s blood / is disaster” (20). In this not-so-far future, O’Reilly’s speaker laments “We should’ve grown gills when given the chance, / I s’pose, but I s’pose that’s the government’s fault.”

It is interesting to read the ocean-izing, whale-calling spirit of menace Callanan’s work against O’Reilly’s seeming despair, “a crate full of flares and no flare gun” (21). The pervasive worry wears on the speakers, and underscores not just contemporary precarity, but a threshold of fatigue that these Newfoundland poets sense coming, a point when governmental mismanagement and climate chaos lead way to a “purgatorial / fog, a prehistoric fog, and all that’s left of this place, my home, / breaks its nails / on the slippery peaks of memory” (20). The de-specified, nostalgia-bearing yesteryear, ‘simple folks,’ time-out-of-joint bullshit that is ever-enlisted to narrativize Newfoundland in the mess that is “Canada,” is mobilized here in the fog that is O’Reilly’s Cassandra-like wailing, as the death of both home and loved ones.

So, perhaps the archetype of the hardy, friendly, Newfoundlanders is borne of some truth, but those archetypes do nothing for the present, for the economic disparity, the vast youth outmigration, and the elevated general difficulty that comes with being alive on a slippery rock that strives to wither you down to less-than-nothing some days. Knowing the poetries of Newfoundland[1] more intimately, the rest of Canada can better learn how to support one another, and how to resist ossifying narratives of “resilience” that encourage us to otherwise take on the burden of governmental mismanagement and capitalist brutalization, to not hold the politicians accountable ‘because we’re tough enough to take it.’

Callanan suspiciously eyes some of these various constructions of Newfoundland-ness, observing in “Exhibit” “puffins…posed as though about to launch / themselves, in their graceless way, / into the graded blue of the display’s back wall, / into the brushstroke line meant to signal horizon”, the speaker’s gaze traveling from the artificial horizon to the “two metallic sprinkler-system / stars” which “shimmer in cool fluorescent light” (56-7). Again, she adopts the perspective of what we might read like someone come from away, in “The model train is undergoing repairs,” where “On a piece of ice like a wadded napkin” (spent trash), “Two miniature seals recline, / no larger than the seagull lighting / on the teal epoxy harbour” and “well-dressed / wives tilt stiff against a car, aquarium- / gravel rubble around their feet” (59-60). The aquarium gravel signals not only the diminutive scaling down of the place, but the outsider looking in, tapping on the glass to point out the things they see. O’Reilly’s speakers likewise scrutinize the worrisome patterning the mainlanders might impose on the home, instructing us in “Making Love to Mainlanders” that “if you want a lover, raise your arm / like one of your vowels, fake a yawn / as you crack / blue jokes about the names of towns / where in suspicion and contempt / you’d be held” (12). Neither poet deploys mean-spirited speakers to chastise the mainland, but both signal loud and clear that they know the way it too often goes, and that these are some of the ways you’d risk alienating their purported (tourism-enforced) ‘hospitality.’

I leave Newfoundland regretting having explored so narrowly, spending time only in St. John’s and its surrounding area, and only briefly in Carbonear to visit a friend a year before starting school. I am very grateful I was able to come here and work with my rock-star supervisor, but I wish I’d just buggered off from school-work now and then, lifted my head up from books to see more than just the one ‘bergy bit,’ that I’d headed to the UNESCO heritage site, visited Cape St. Mary’s when there were actually birds there. But, knowing I’ve missed so much of the joy here, I know too I’ve known friendship, and hospitality, and I can return to titles like those these two poets have shared with us, head in book again, and feel the radiating heat of hospitality like that of a freshly boiled cup of tea.

[1] Of course let’s acknowledge that these are white, settler-based poetries I’ve reviewed here, and are by no means an exhaustive or comprehensive survey, instead merely two books likenesses worth noting, which address some of the ways Newfoundlanders live that I am familiar and comfortable enough with to write on.